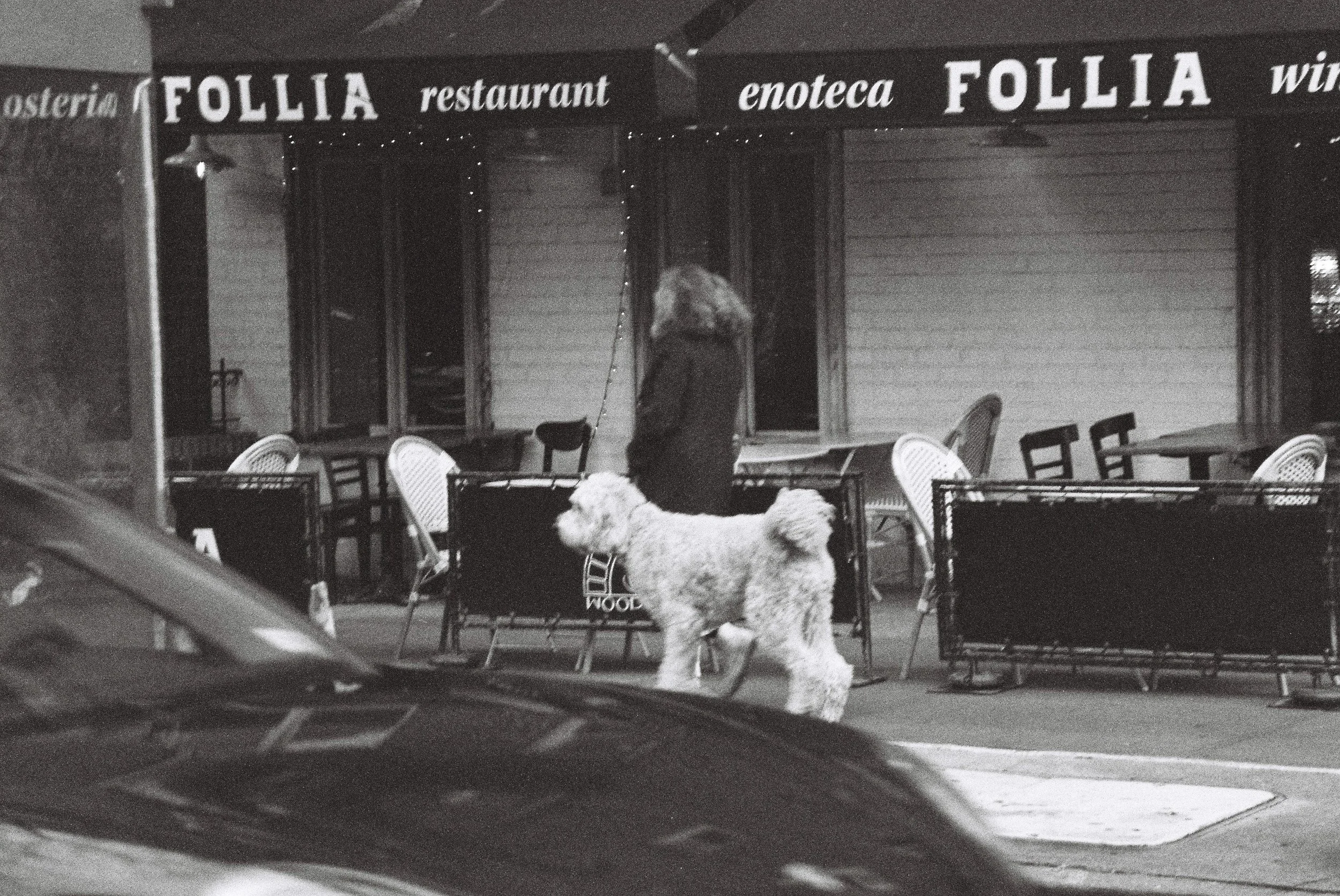

August 15, 2024 - “Untitled” by Masha Vasilieva

Masha Vasilieva is a film photographer based in Brooklyn, NY. Her works have been exhibited at Soho Photo Gallery (exhibition “Krappy Kamera”, 2022) and Glasgow Gallery of Photography (exhibition “Blue”, 2023). She is fascinated by every day life, double exposures and film photography experiments. More of her works are available at https://www.mashafilms.net/

August 14, 2024 - "sometimes, pirates." by Linda Dolan

i haven’t been able to find my umbrella for a while now

and until today it hasn’t really down-poured. i’m afraid

that at counseling tonight, chris will say he’s leaving,

and it feels like the right place to do it.

i miss my dad again with the stabbing pain.

and it’s been a few months since my heart surgery now.

my bag is too heavy with the smoothies and a glass jar of chili

and the books and computer for the day. and the rain is fat drops

plopping their way into my bag and onto my computer

and i realize i’m walking very slanted and very cold, proud

that i’m doing the only thing i can.

but numb.

and then i transfer to the r train at times square.

and from 42nd street to 8th street, the conductor speaks pirate:

this is a brrrrooooklyn boouund arrrrrrrrrrrrr train.

and each stop, i think he might laugh or trip up. but each time

i’m grinning, and he’s: arrrrrrrrrrr train. next stop twenty-tharrrrrrrd street.

there are moments

in this world

that give me strength enough

to cry.

“sometimes pirates.” is a poem from the author’s chapbook i’m probably betraying my body (Bottlecap Press, 2024)

linda harris dolan is a poet and editor living in Lenapehoking/Brooklyn. As Poetry Instructor at NYU Langone Health, she leads writing workshops with nurses, medical students, caregivers, and pediatric patients. She is Assistant Poetry Editor at Bellevue Literary Review. She holds an MFA in Poetry from NYU, where she was a Starworks Creative Writing Fellow. Linda is the recipient of fellowship support from The Rona Jaffe Foundation, Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, the Starlight Foundation, Brooklyn Poets, and the Ruth Stone House. Her chapbook, i’m probably betraying my body (Bottlecap Press, 2024) traces the experience of one person in a body, amidst a family full of bodies, navigating life with a genetic heart disease.

August 13, 2024 - “The Ivory-billed Woodpecker” by Miles Greaves

Which it does not, it was the evaporation of those river-bottom forests, which vanished, like hair from a leg, I remember those trees weeping tears of sap, as the saws neared their bellies, but they were halved anyway, anterior bark to posterior bark, xylem and phloem. And I remember helping shave those forests smooth to the stone, as if with an apple peeler, the flesh, the topsoil, the loam, the bedrock, tubers and moles, fossils and coffins—they curled in front of us like pencil shavings, until we reached the Gulf, and then collectively puffed it all into the Atlantic, and ran our palms over the continent, clean as a desk. Behind us, the yellow land was peppered with Ivory-billed Woodpeckers, who were trying to perch on the now-nonexistent trees, but were hailing out of the sky, and swimming clumsily along the ground, and mewing. Seeing this, some men and some women looked away, as if from their naked father, because these used to be the Lord God Birds, or Diana bathing, or the bare eye of a singularity, or the number i, or the Entertainment, or the sun, as delineated as dominoes, with bills of bone, and a crest like a sail of thundering blood. And so I stepped, bird to bird, and with my heel I pressed each one of their skulls into the earth, as if forcing them to become ostriches, until the species entire lay where they were, like crops, with their tails spiking unattractively into the air.

The Passenger Pigeon used to dim the air with their flocks, days long in the passing. I would see them cresting the mountains like a storm, or static, cooing, and I’d watch the townspeople flee to their pigeon-shelters, while old men, caught in the street, would inhale the birds, or hold their breath, and try paddling vertically through the feathers and beaks, but inhale, always, and settle toward town again. And when the flock thinned, the townspeople would breathe into the old men’s mouths, and pump the birds from their lungs, but it was always the pigeons that they wound up resuscitating, the birds would flap from their mouths and rejoin their herds, dizzy. But I would don fishbowls and pots and wade into the flock, with tennis racquets and golf clubs, and swing, it was like rowing over tar, the pigeons knotted on my clubs, like seaweed. Sometimes, at the instant of their arrival, I would throw mousetraps and beartraps and nails into the air, and sometimes I’d wait behind drills, or industrial fans. I would discharge rifles into the cloud, to watch the brief tube augured into the flock, which would hold momentarily, then close. As the species died, though, the tunnels lost clarity, by the final pigeon it was arguable that the tunnel had been inverted so as to encompass, backward, everything but that last bird, so out of philosophic curiosity I shot it through its canary cage in the Cincinnati Zoo, but there was no lightning, no shift in things.

The Carolina Parakeet would perch on telegraph lines and eavesdrop; pooling the word or two that each knew of English, like “cracker,” or “good,” or “extirpation,” and decode, piecemeal, any communications concerning the genocide of birds. Then, hearing enough, but being unaware of their English name, they tried fleeing North Carolina, but broke their necks in the air above the Tennessean border, like green snowflakes trying to flee their snow globe. The remainder of the parakeets forswore squawking and froze like mimes in the green trees. They might be breeding today had I not begun publicly fawning over women with emerald feathers in their hats, and then women with two emerald feathers in their hats, and then three, until the women looked like emerald bonfires, and postures were ruined, but the fashion continued to mature anyway, until the Carolina Parakeets were skewered and mounted, whole, onto the tops of the hats; and until the body of the hat-proper was discarded, and the bodies of the birds were folded into the shapes of hats, alive, so that the hat would squirm, and squawk. This was the fate of the last Carolina Parakeet, which a milliner stitched into the hat of a young socialite. Its neighbors on the hat, which towered, like a tall brain, had died, like city lights in reverse, leaving only this last ambassador, twisting by a foot from the brim of the hat, for two days, stretching at the socialite’s lunch.

The Labrador Duck died like a rich family leaving a poor neighborhood, it freed the napkin from its collar and left the restaurant, with a valise of its DNA, which isn’t sold anywhere, I couldn’t even lure the duck closer to the shore, to the strangling hands there, because it disdained bread, so I had to wade after them in fisher pants, and even then they wouldn’t move, as if fleeing were undignified, I would just submerge their heads with a single casual finger, as if plugging a leak. One afternoon I looked back at the shore, where the men and women were supposed to be killing ducks, but saw that they were eating from picnic baskets instead, as if the duck supply were exhausted. Then I saw a man, who seemed to realize this too, and I watched him pull a drowned duck from the water, and try wringing it into life, but he couldn’t. And now that duck is endangered anyway, being the final Labrador Duck corpse in existence. The man must, then, keep it dead. Each evening he repoisons it, and before breakfast he reannihilates it with a shotgun, he brooms the feathers into a vat of rubber cement, and adds the duck’s body, and stirs, and sculpts, with the gruel, a fresh duck, which dries on his fire escape, like a pie. When not killing it, the man sits it on a dish of turtle eggs, or clips it to a clothesline, and hoists it between apartments, as if for a walk, or he takes it to the park, to show it living pigeons, in order to shame it.

The last Eskimo Curlew was consumed by hagfish, at the bottom of the Berring Sea; the last Bachman’s Warbler was disassembled by ants, outside of Orlando.

The last man to see a Great Auk breathe was Karl Kronson, who decapitated it with his ship’s auksword, a saber as bladeless as a whiffle-ball bat. The day before the extinction Karl was mopping on a whaling ship. He mopped vigorously up to a coil of rope, and turned proudly, but a ribbon of olive and maroon stains extended in a tract behind him. So Karl upended his mop and squinted into its locks, but he found no tomatoes there, no chalk, no gremlins, so he planted the mop onto a single stain, as if into a whale, and mopped in place, aggressively, until forgetting the time. But when he finished, the stain was as healthy as it had been before the mopping.

A bundle of moppers edged into his periphery, and passed, like a busy cloud of elbows. Behind them, like a clean rattail, the planks beamed, like long ingots. The moppers continued to the distant end of the deck and stopped and waited for Karl with their elbows on their mops. Karl mopped after them, along the border of their pristine trail, dirtying it, which forced him to reiterate and reiterate and reiterate his own inferior mopping. When he reached the crowd, Karl said:

“I finished an hour ago—this is my second time through.”

The moppers laughed.

“And you put back the old stains,” said one.

The moppers laughed.

“That’s harder than getting rid of the original stains,” said Karl.

The moppers laughed.

“No,” said a mopper. “You’re just a terrible mopper.”

At dinner, Karl stared at the table between his forearms.

“Maybe you’re not using water,” said a sailor, but ironically.

“Maybe it’s your mop,” said another sailor, but also ironically.

“At least you’re a good auker,” said someone else, but this was also an insult, because only the most inessential sailors were told to collect auks.

Then the captain came in. His eyes summersaulted over the crew in inexpressible disbelief. He held his arms in front of him, as if trying to hug something, but he couldn’t, so he dropped his arms.

“What happened, Karl?” he asked.

Karl spiked his napkin into his rice and stood. He saluted passed the captain, on his way to the mop closet, as if to reswab the deck.

“Wait wait wait,” said the captain, and he gestured Karl to a stop. Then he handed Karl a saber, as dull as an elephant tusk. “Just kill auks tomorrow,” he said, “and don’t try mopping them.” Then the captain made a gesture of ineffability, and left.

The auks’ last island was a wart of stone on the Northern Atlantic. The next morning, the whaler anchored off that rock and lowered a rowboat onto the ocean, with Karl inside. Karl, who was also a poor rower, rowed towards the wart in a series of semicircles, hearing the crew behind him chant “Auker! Auker! Auker! Auker!” until he could only hear the ocean; and, then, until he could only hear the auks. The planet’s remaining Great Auks had convened on that island, as if it were the only wood after a shipwreck, their weight pressed the island into the ocean, their feces softened it, they congealed and throbbed in aukpiles forty and fifty auks thick, their screaming sent whitecaps away from the island, they were copulating accidentally. Karl killed eleven just docking, and he crushed twelve just stepping onto the island, and as he killed auks the remaining auks ripened, subtly plumper with the increased percentage of the species that they represented. Then Karl walked into the center of the island, and gripped the saber like a baseball bat, and shut his eyes, and swung for several minutes. And as he did, he noticed, only, that the sound of the auks was fading, as if he were turning down their volume. When he opened his eyes, he was standing in a red and white and black clearing of mulch. The remaining auks were teetering in a dome around him, as if Karl were inside an igloo, but then they collapsed, and spilled toward Karl, curious. So Karl shut his eyes, and swung again, and the auksounds faded again, and faded, until Karl sat, panting, on a couch of dead auks. Fifteen or twenty obese auks remained, propelled into the ocean by the melee. They swam, smiling, back to the island, and beached themselves, and toddled across the rock, to Karl, holding aloft their fetal wings, and pressing their ribcages into Karl’s shins.

“I’m tired,” said Karl, “someone else can kill you,” and he kicked them away.

But the auks insisted, like the Zone Hereros, and so Karl stood, and took individual aim, and murdered each of the last auks, including the final auk, by this time as large as a dalmatian. At that, the chanting of the crew came back to Karl, over the water:

“... Auker! Auker! Auker!...”

Mentally, Karl blanketed the “auk” side of the chant with “mop,” but the illusion would not persist. Then Karl remembered that, in the minutes between his birth and his naming, he had cycled through the nearly infinite possibilities of being—alligator, toaster, Ayre’s Rock, Pythagoras—like a blurring slot machine in the crook of his mother’s arm. But then “Karl,” she had pronounced, and he had been fixed, for the duration of language, by “Karl,” in all possible universes.

Karl sat, jealous of the Great Auks, who were now absolved of their personal mediocrity, because there wasn’t a first name among them, so only the Auks were extinct, plural, like losing a color, not a crayon. And this meant that each singular auk, even the least great, was now free to excel at catching fish, or preening, or fending off polar bears—or they could become manta rays, or cubes of granite, or cacti—while even in death Karl would still be a poor mopper, and a poor sailor.

Karl made a similar complaint to me on the day I came for him, to swallow him. He lay on the deck of a ship, bent, like a spider, after falling from the mizen mast. He whispered up to me:

“Now I’ll always be a poor mopper.”

But “No,” I said, “in seventy years’ time you’ll be as unremembered, and as infinitely variable, and as good a sailor, as each of the Great Auks that you harvested.”

And then something similar happened after I swallowed the last of Karl’s species, a sick woman in a waterless cavern. First I savored the sharp taste of the whole of human culture, which stopped existing, and became unrecoverable, at the moment I swallowed her. And then the universe screamed once, as if mourning the loss of humanity, which meant that its awareness of itself would dim—no more equations to define it; no more songs to celebrate it. But within the hour it had flattened back out into nothingness, and by year’s end it was remembering mankind, only, as the species that had been driven into extinction by the Ivory-billed Woodpecker.

Roger T. Peterson, A Field Guide to the Birds of Eastern and Central North America at 188–89 (4th ed. 1980).

Miles Greaves is an attorney living in Sleepy Hollow, New York, with his wife and two young boys. A story of his won first place in Zoetrope: All-Story's Annual Short-fiction Contest, and others have appeared in Tin House, Jersey Devil Press, and Storybrink. When he gets some free time, Miles enjoys birding, playing basketball, and watching “The Challenge” with his wife.

August 1 - 8 is READING WEEK!

Curlew accepts submissions on a rolling basis but we are taking the next week to focus specifically on reading / viewing new submissions, so send ‘em in! We publish poetry, fiction, and creative non-fiction, which includes nearly all forms of reporting and journalism. We also accept photography and visual art.

Accepted submissions will be published as part of Curlew Daily with the possibility of also having your work featured in our next print issue.

Submissions may be e-mailed to Info@CurlewNewYork.com and will be read and viewed upon receipt of the $7 reading fee, which can be made on the submissions page on our site. Thank you to our submitters, contributors and readers for your interest and support!

All our best,

Curlew

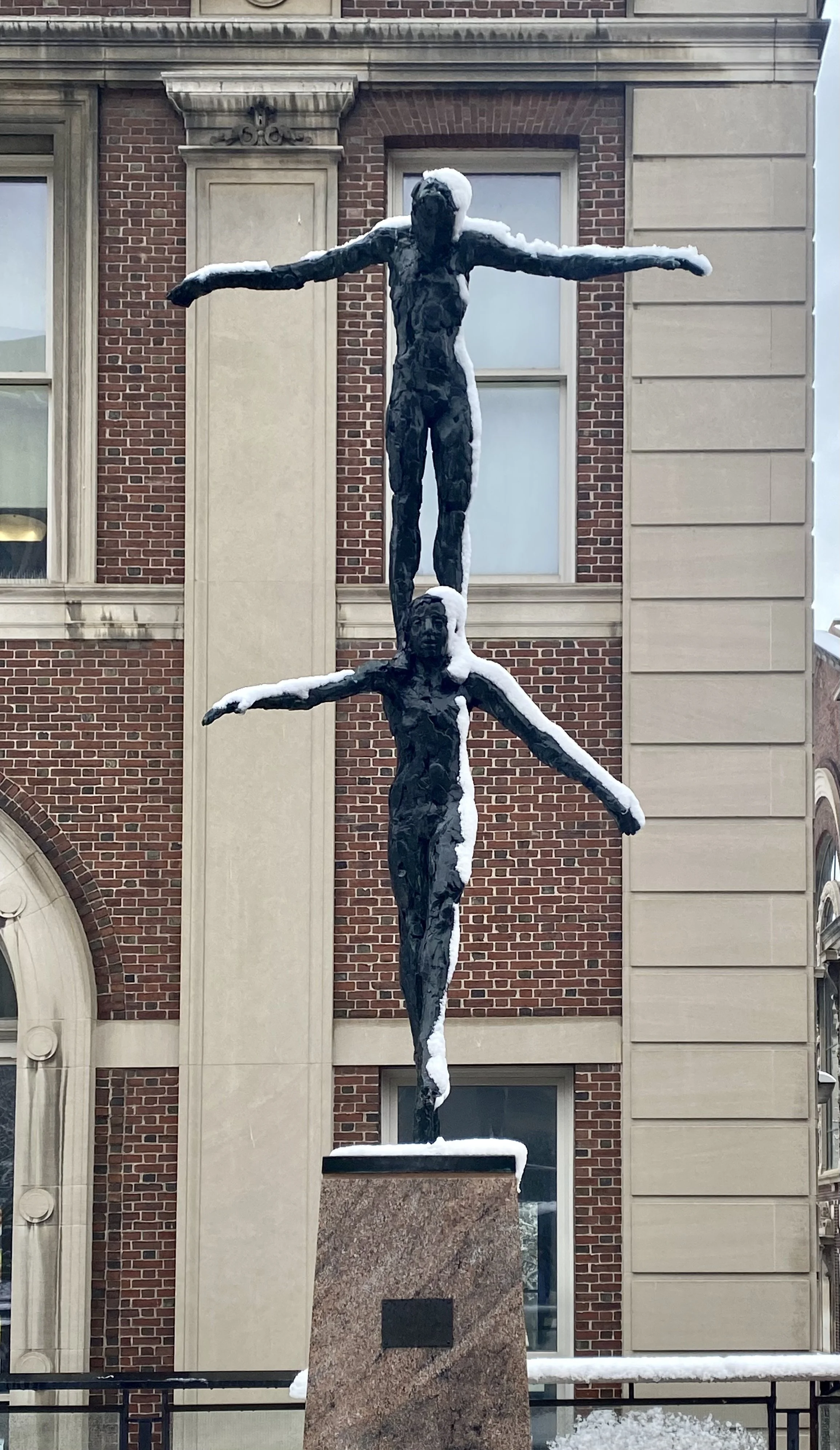

July 31, 2024 - “Tightrope Walker: Two” by Ray Zhang

Ray Zhang is currently a student at Columbia University who has studied under Ernest O. Ògúnyẹmí and Lisa Hiton. He has been recognized by the Health Humanities Journal of UNC-Chapel Hill, Thimble Literary Magazine, and the New Zealand Poetry Society. In his free time, Ray enjoys hiking through the Michigan wilderness and fishing on the lake shores.

July 30, 2024 - “Summer Has Nearly Begun, and Summer Is Nearly Over” by Alivia Francis

Yes, indeed.

A brief embark

A burst of passionate sincerity

Crying out into the dark

"And after that another"

Yes, indeed.

Bare-legged

under an umbrella,

Trudging home

After our dance

"Once upon a time we were Europeans"

Yes, indeed.

Held together by tangled roots

We turn for home the future coming,

Now it's so clear,

"I remember, I remember"

Yes, indeed.

I am continuously inspired by the lives of those around me, as well as by the several lives I feel I have accumulated within myself during my 25 years thus far. My poetry is a collection of my tumultuous thoughts that are feverishly and sloppily written mostly in pen, and mostly when I am least expecting them. I frequently attend poetry readings at The Music Inn and have a collection of personal zines that are soon to be self-published under my name, as well as a few small unpublished collaborations with other artists. — Alivia Francis

July 28, 2024 - “Summers in Guangdong” by Ray Zhang

My grandpa is cooking tonight and shows me how to pick the best eels.

He brings me to a thousand black tongues dancing in ashy buckets, growing plump under humid heat.

I reach in, ready to teach my fingers the feeling of slime, but he pulls my hand away.

He points to pairs of red gills and dark pupils, noting how they curve crests atop each other.

The fishmonger gives him two as I grasp his arms.

Tastes of summer brine etch in my throat as I wait to wash it away with eel congee.

July 27, 2024 - “Water and stone”

You spend so much time thinking about being a person that sometimes you forget to be one. Even now, you leave a moment of bliss to come write this down before it’s gone, and by the time you are out of the pool the right phrase has left your mind, and if time were really ours we’d be able to go back and now you are here wishing you could read your own thoughts like a book. You disappoint yourself by being human. You smoke some more and go back to where you were sitting, on the steps in the pool, where the sun shone and you remembered to close your eyes and feel it. You do it again, you close your eyes and listen to the constant flutter of water slapping against stone, to the lawnmower next door, the car pulling into a gravel driveway, the pool water again, the cawing of some bird, the squeaking of another, water and stone, a car door slamming, two doors and then keys. You see him through the patchy stalks of wood between your yards, see a child picked up and carried inside, a woman emptying the trunk, her and the man both holding large coffees. They walk right when you think they’ll go left, and you realize you've been looking at their garage this whole time, not their house. The house is to the right, past a thicker bush that does not let you see through it, and watching them disappear behind the green mass, you enjoy the idea that you are nothing to them.

July 26, 2024 - “Tightrope Walker: One” by Ray Zhang

Ray Zhang is currently a student at Columbia University who has studied under Ernest O. Ògúnyẹmí and Lisa Hiton. He has been recognized by the Health Humanities Journal of UNC-Chapel Hill, Thimble Literary Magazine, and the New Zealand Poetry Society. In his free time, Ray enjoys hiking through the Michigan wilderness and fishing on the lake shores.

July 24, 2024 - “Where we’ll stay”

Patty likes to take tab at the start of every season and walk her favorite trails. She’s been doing it since the divorce. She told May that trying it with her that one time in the woods, in the cabin by the lake, that day when Patty’s parents weren’t home, and Allan and Bobby had blown them off for beers in town, was one of her favorite days. Patty’s uncle had been there the week before and offered them some and May accepted but when Patty had raised her open palm she slapped it away, saying they had to save it for sometime special, when men weren’t around, is what she meant, and so they had stored the tabs in a jewelry box on Patty’s dresser in her room at the cabin and asked Patty’s parents if they could have a sleepover the following weekend, saying we are running out of time, and who knows what will happen after school ends, we may not ever see each other again and even Patty’s parents had to roll their eyes at that because where did these two think they were going, but still they said okay and for a saturday the place was theirs, and so they stripped down to cotton undies and sunbathed on the rocks by the water, and Patty put mud on her face and walked through the woods for a long time, while May made the sun room an art studio and drew at a desk that was made of wood that came from these woods, and by the time Patty came padding through the screen door, they had both decided to never leave, and neither of them ever did. The story sits like so many others they have told, they type that leaves you feeling safe and sad and stuck someplace you sort of don’t mind being stuck in.

July 21, 2024 - “First Marriage”

You hear Patty’s loud laugh and think about how much nicer it is when she’s here. May becomes less of a mother and more of a person, and the boys are calmer too. Patty brings a little bit of her brother with her wherever she goes, and everyone feels lighter because her cackle sounds just like Bobby’s.

Patty says she was married to May first, citing the time they had built an altar in the woods behind the house and had Bobby tape a white strip of paper to the neck of his black tee shirt to officiate.

You wonder what it would feel like to be family from the start. You find it both envious and impossible, that they will all be happy here forever.

They’d written their own vows, had read them out loud as Bobby tried not to laugh, and then they sealed the ceremony with a kiss – not a real one, May would insist – the kind where you grip each others cheeks and put your thumbs over the others lips and then pressed your lips to your thumbs and sway together in an imitated embrace. Schoolgirl stuff, she says, blushing.

A decade later, on May and Bobby’s wedding day, Patty read the vows they had written as girls and even the groomsmen cried. You can’t imagine having so much love for so long and you think, on her best days, this is why May wants you to have a child so badly. She knows what you are looking for and she is saying here – there’s a way to have that. But mostly, May just wants a baby. Mostly, she just wants another go, and on your best days, you almost want to give it to her.

July 19, 2024 - “Spring calling” by Ellis Dickson

I’m in this good sun

It eats my eyes like this without teeth

In my very closed interior I see clearly

In yellow, orange and gold

It shines from the garden of the meadow of the stream

Through the filter of my tight skin

Eaten away by this beautiful sun, so full of expectation

Soon the tomatoes will burst

And then the strawberries and then the plums

And then my skin

Ellis Dickson is working on identity and home through poetry, short stories and novels. She is interested in light and colour in the representation of the familiar. A few texts are published from time to time in general literature, poetry and science-fiction.

July 18, 2024 - “Shade Part II” by Kyrsten Jensen

She bloomed time and again;

those rare, fragile

white flowers spreading shyly,

pink centers peeking out

and we plucked them,

one by one.

We braided them into our hair,

made wreaths and delicate crowns

and left them to dry

and shrivel, shrink and

shrink and

crackle under our feet.

The blooms ceased to be

beautiful things to us—they were the

passing of time,

the curl of mist as it

burns away to nothing.

We did not save them,

or press them between the

pages of thick books.

We did not love them,

and we did not notice

when they faded.

She reaches outward still.

Her shelter has not shifted

nor weakened.

We take limbs, and blossoms,

and leaves—

build and break and take

until she is bare

and still, she stands on.

She protects the quiet,

and will until the glint of steel

steals the shade away.

And we will spread our hands

across the smooth,

barren surface—what is left

of a mighty presence,

and trace the map of the

rings left behind, close our eyes

and read them like braille,

fingertips living a story in a language

we forgot.

We will remember the blue quiet,

and the soft peace of her.

We will craft a crown of

flowers—press them and

seal the petals, thin as

butterfly wings, into a pane

of glass.

We will stretch our fingers,

bend them,

practice the motion so that

one day,

our own shade

will be another’s peace.

We stretch our fingers,

curled up to the sky.

Maybe one day,

the stars will read

the deep circles of our story,

trace them with fingers of

light, and

somewhere

she will smile.

July 17, 2024 - “Other than remembering”

“You know what I used to smoke?” she asks, handing your lighter back to you, studying the lit embers for a moment before bringing the cigarette to her lips, like she was deciding if it was worth doing, if doing it made her more like you than she would have liked.

“Virginia Slims?” you guess, making May laugh out a cloud. She shakes her head and looks at you like she knows something you never will.

“These,” she says, with the cigarette between her teeth, grinning wide like she has delivered a punch line. But for once you don’t think she is trying to teach you a lesson, you don’t think she is doing anything at all, really, other than remembering.

July 14, 2024 - “Small human things”

Loneliness lasts longer here, where it’s quieter, where the world is not constantly moving around me, but where I am moving through it. My body wants to be drawn towards another with magnetic pull, and I keep stretching my arm out in bed to feel the emptiness of the other side, and I am not mourning much, but am thinking it would be nice to have someone there, and it is hard when I dream there is. I have to lay there a while when I wake up and try to leave the knowledge of another body behind — but there are perks to being alone like this, to existing somewhere new. Last night the whole house smelled like garlic, and it was me cooking and here, I am the type of person who grocery shops, starts laundry while dinner is on the stove, does a sink full of dishes, then sits down with a glass of wine, and I don’t recognize myself when I do small human things like this but I am learning to, because I understand why they’re done. It feels nice to feed yourself and clean up afterwards.

July 13, 2024 - “Shots were fired during a campaign rally in Butler, Pennsylvania”

A former American president was shot at today. Someone tried to kill him. Shots were fired during a campaign rally in Butler, Pennsylvania. This is the line where the writer describes where they were at the time. This next line should be where the writer explains how the events have affected him and what he believes it means for the direction that this country, the United States of America, is heading in.

Here, the author might make note of the fact that from here on forward, Juneteenth will consistently be celebrated only a few weeks before July 4th’s Independence Day. He might observe that one political party embraces the ideology of Independence Day far more than the reverent reflections that a celebration of Juneteenth might invite. At this point, here, the author might explain that the thought of a former president of this country facing an assassination attempt feels incredibly unsettling, regardless of whether said former American president has consistently said words to incite violence and has also consistently refrained from condemning violence.

The author, here, would do well to compare the temperament of the former American president who was shot at during the campaign rally to the temperament and record of the current American president. The author might note here that it’s obvious that the temperament of the current American President seems a lot less likely to incite more violence than the temperament of the former American president who was shot at during a campaign rally today. The author should also note, here, or somewhere around here, that there was someone who was in the crowd who did lose his life while attending the campaign rally as a result of the shots that were fired. The author should also mention that the person who tried to assassinate the former American president was twenty years old and is now dead, having been shot by individuals who were responsible for protecting the former American president during the campaign rally.

This would be a good line for the author to reflect on what today’s assassination attempt may or may not mean for the upcoming presidential election in November. Having made such observation (or lack thereof), this would be a good line for the author to explain that the election, given today’s events, feels at once a great deal more important and also a great deal less.