I. FIRST IMPRESSIONS - GRAND CENTRAL STATION.

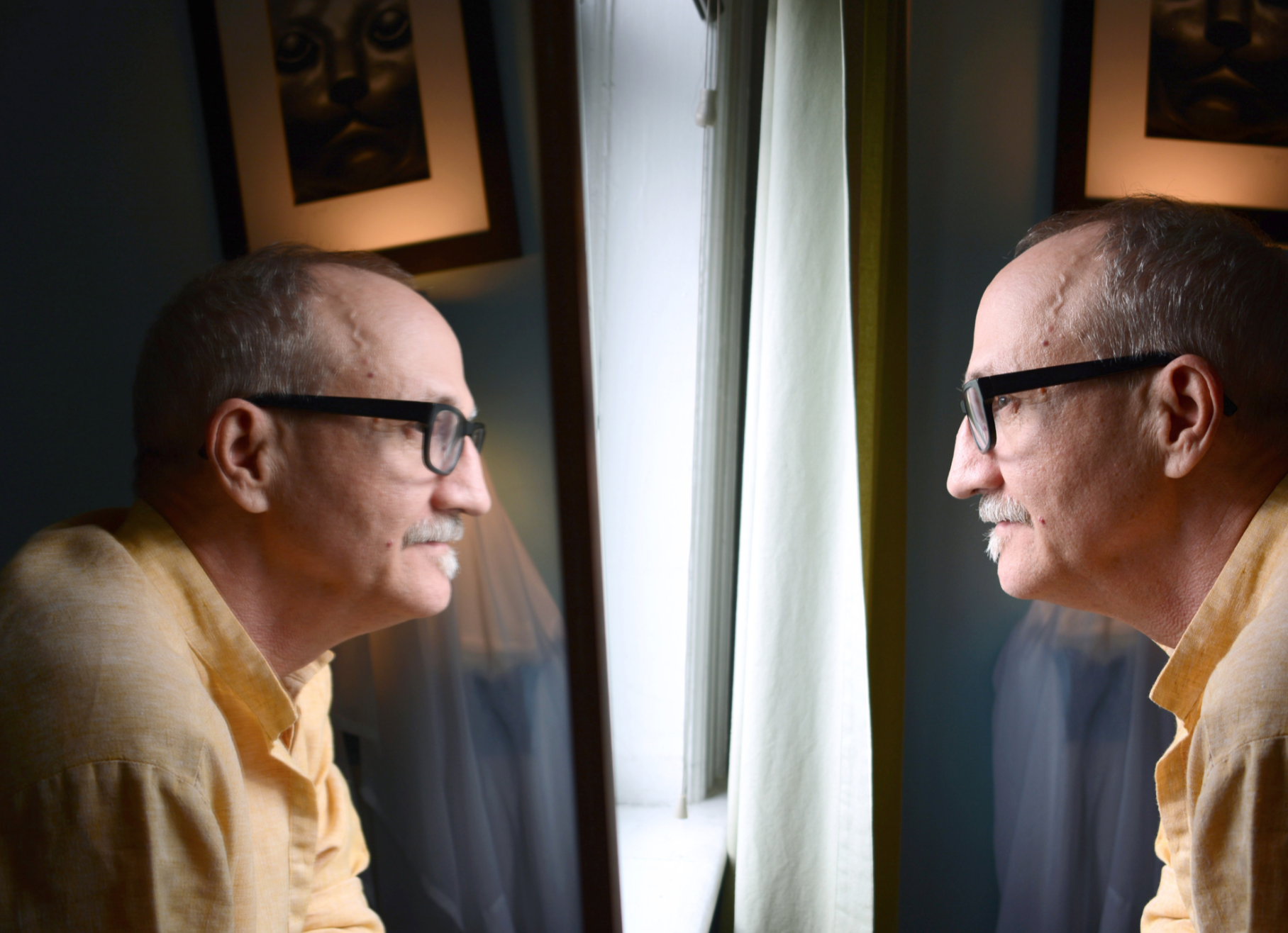

Robert Englebright moved from Chicago to New York in 1999. His first apartment was in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. By the time the millennium turned, he had spent over a decade learning and practicing the craft of commercial photography. This fall he’ll be fifty-eight. He has broad shoulders and a strong handshake, and wears blacked-rimmed glasses that he often pairs with a black ball-cap or an ascot hat, which he takes off whenever he hears a thought or a phrase that catches his interest. On a Saturday last November, I met Englebright in the middle of Grand Central Station.

In addition to his own work as a photographer; Zigna – a commercial photography firm that originated in Denmark –– brought Englebright on board three years ago. When they hired him, he was already working through his three-to-five year plan to move back to Chicago. So when they offered him the opportunity to manage and train their photographers, Englebright told their managing director that he would only take the job under one condition: that he would eventually help the company open a franchise in Chicago, and that they would move him back there in order to do so.

That afternoon in November he had on blue jeans, a black jacket, black ball-cap, and orange Nikes. I walked over to meet him and when I shook his hand, I was impressed by the strength and certainty of his grip. He has a real “good to see you, put her there,” sort of handshake. In his left hand he held a take-away bag that I asked about -- “Peruvian food,” he said, “A little on the salty side, but still, tasty.” We looked for a place where we could enjoy some of the sunlight. Eventually we found Perk Café, a small and quiet coffee shop on East 37th Street, between Lexington Avenue and Third Avenue. We ordered our drinks, found a table by the window, and started with real estate.

I asked him about his work shooting interior spaces for real estate agents. “With real estate photography, it’s a mutual endeavor, I’m the photographer, but I can’t just be thinking of myself when I’m taking the photographs,” he said. “I have a client who has hired me for a specific reason, so I have a different hat on as a real estate photographer, rather than when I’m just shooting on my own.”

As Englebright had previously spoken of shooting spaces for interior designers, he was quick to compare that work with the work of shooting for real estate agents. “With real estate photography, it’s more of a numbers game. It’s shooting a lot, but it doesn’t take as long,” he said. “Whereas when photographing for interior designers, I’m able to charge a lot more, and it’s just one job that could be an entire day at a location. And with real estate photography, you’re trying to con- vey the spaciousness of an empty room –– or the flow, the layout of an apartment. You’re trying to do that with photography, so that people can look from one photograph to another and get an idea of how the rooms fit together. Whereas, with interior designers, you’re trying to show off their work. You’re trying to show off surfaces, patterns, fabrics, their use of color, how they coordinate it, fixtures, all of that stuff. So it’s a different animal. You’re coming in close on things, and there’s different composition elements that you take into account.”

When I asked Englebright what criteria should be used to evaluate the quality of one photograph against another, he expressed the importance of taking each photograph on its own merit. “For the most part it’s subjective, but there are criteria that can make a good photograph, but then you could see a photograph that seems to be counter to all of that, and still be a great photograph, but then when you get behind it, you realize that the guy who took the photograph is a really good photographer, and knows all of those rules and criteria, and is breaking them intentionally.”

Although we pulled at this question for a short amount of time, it was clear that Englebright was more interested in the question of what it actually means at all, to be a photographer. From 2013 through 2015, he spent a great deal of time growing his own work as a photographer. These efforts can be seen from the photo and journal blog that he included on his website, which features a series of posts beginning in September of 2013, then rising and much like a bell curve, the frequency falling off again by the end of 2015. Englebright mentioned that he had tried to keep up with the blog in order to grow his own private work as a photographer, but that as more time passed, he grew more frustrated by the nature of blogging. “It just feels so self-involved,” he mentioned, “as though I’m just writing and writing things about my own work that no one will ever read.” Even so, one post from March of 2015, “What is it to be a Photographer?” captures the plight that Englebright finds himself within, as a modern photographer.

It’s now easier to claim to be a photographer without actually being one. One doesn’t need a dark- room. One doesn’t need to set apertures and shutter speeds. Cameras are cheaper (the amateur ones are cheaper -- the professional ones are more expensive). The boundaries have disintegrated. And the elitist stance that I may appear to be taking by having to define what is a photographer is made because of the effect this is all having on the profession. I can’t help but feel like the bar has been lowered regarding what it is to make a living as a photographer and the possibilities of doing so.

He expressed similar thoughts when we met in person. “It’s a different business than what I came in doing, definitely. Companies would hire photographers, and most of the commercial photographers had training, they had learned from the photographers before them. Now people pick up a camera and it’s like, wow, I’m a photographer. And companies take advantage of the whole Instagram, Twitter thing by dangling them in front of people who take pictures -- ‘I’ll give you this watch and you go out and photograph it,’ and then they end up using it for advertising, and these people -- the guy who took the photograph of the watch has no understanding of usage, of ownership, copyright, so he’s just basically giving his images away to this company without negotiating any usage fees, or rights, or anything like that. And this has just upended what it means to be a commercial photographer.”

Englebright didn’t start taking pictures until he was eighteen. “I didn’t really pick up a camera until I was a teenager. But I was always into drawing, and painting, and ceramics, and jewelry making, all of that stuff.” He mentioned that when he did first start taking pictures, he was most interested in the abstract. While Englebright’s collection of images includes a number of intimate portraits and broad shots of cityscapes, his Second Impressions series has a way of catching people’s interest right away. The Second Impressions photographs are blurry, or as Englebright would at one point pause, to gently correct me: they’re “out of focus.” The subjects within the photographs exist more as placeholders for the presence of a human being, rather than as human beings themselves.

In “Two Women Standing in Times Square” two women stand on a New York City sidewalk, just before the crosswalk. One woman appears to be dressed in a white top, with a gold skirt, while the other woman seems to be wearing a black dress. They’re both wearing heels. A ray of sunlight falls into the photograph, from just in between the buildings that stand on the other side of the crosswalk, which is covered by shade. A large building that’s just across the way from the two women stands in the way of the sun. On the side of the building you can see what appear to be orange letters and numbers along a ticker display.

The photograph is out of focus, but still, the women’s presence within the photograph tells us that there’s a story unfolding here; something is happening. And because we can see just enough, and imagine just enough, a certain want and desire to solve the mystery, to bring these two women into focus, intensifies our interest.

I was interested in hearing Englebright’s take, as to what inspired the Second Impressions series. “The idea was that photography by its nature is very representational -- and it’s very much a product of technology,” he said. “It was born in the industrial revolution and the advances in photography and technological advances have always mirrored one another as we go. The thirty-five millimeter camera, the digital camera. There have been these revolutions, so Second Impressions was my attempt to try and wrestle the medium away from the representational and to somehow convey what it’s like to try and remember something. Because you can never remember the details, you just remember the outlines -- the sort of basic forms in your memories. Maybe you’ll remember

a specific detail, but for the most part there’s a generality. And so that’s what I was trying to do with

Second Impressions.”